Benign Myths in Financial Advice

This week’s episode of Patrick O’Shaughnessy’s Invest Like the Best podcast featured three-time (!) guest, Michael Mauboussin. If you’re not familiar with Michael’s work, he is the Director of Research for BlueMountain Capital Management and is a national treasure in the investment industry. Here are a few samples of his recent research:

What Does an EV/EBITDA Multiple Mean?

Procyclicality and Its Extremes

The whole episode is worth a listen, but towards the end of the conversation they touched on the concept of “benign myths” that pervade our lives. Here is Michael on the subject:

These are myths in the sense that they’re not really based on anything true. But they’re benign in the sense that they’re not harmful. And the key to these benign myths is that they motivate people. So I think a lot of stories, or a lot of narratives, could probably be in this category of benign myths. There’s really no empirical foundation for these things or facts behind them but they get people motivated to do the right kinds of things.

He specifically cites Jim Collins, famed management consultant and author of Built to Last and Good to Great, as an example. Michael has been critical of some of Jim’s research methods over the years, but also finds him to be a great guy who is very thoughtful in his work. While his analysis and methods may not meet the most rigorous standards, they are somewhat negated by the positive impact he has on people. Corporate executives and managers *feel* better and are motivated after spending time with him. It might not be the best science, but people are often better off following their interactions with Jim.

That got me thinking, what are the benign myths that exist in the financial advisor community? Perhaps there are some rules of thumb, or other common tactics regularly used by FAs that might not hold water intellectually but can still lead to better results for the client. After more than a decade in this business, it’s no surprise that a few examples immediately came to mind.

Dollar-Cost Averaging vs. Lump Sum Investing

Earlier this year, Nick Maggiulli wrote two epic back-to-back posts on the subject of Dollar-Cost Averaging on his great blog Of Dollars and Data:

Shot: Even God Couldn’t Beat Dollar-Cost Averaging

Chaser: How to Invest a Lump Sum

Read both of Nick’s posts in full for all the details, but the TL;DR takeaway is that on average and over time:

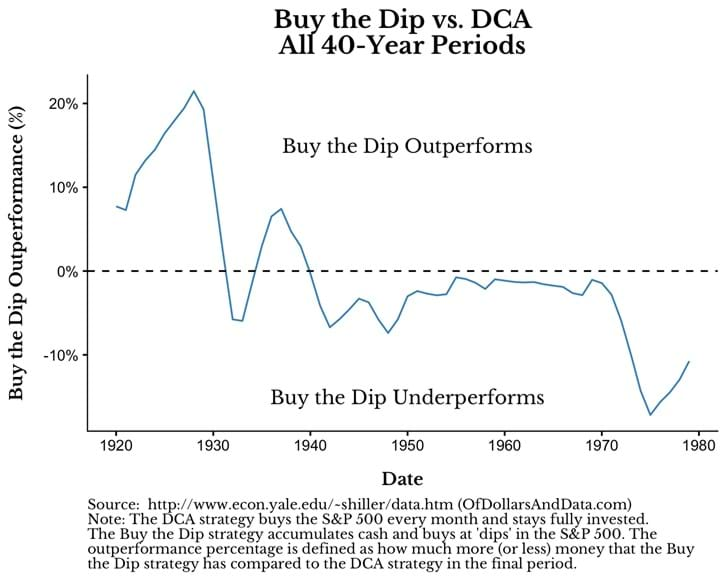

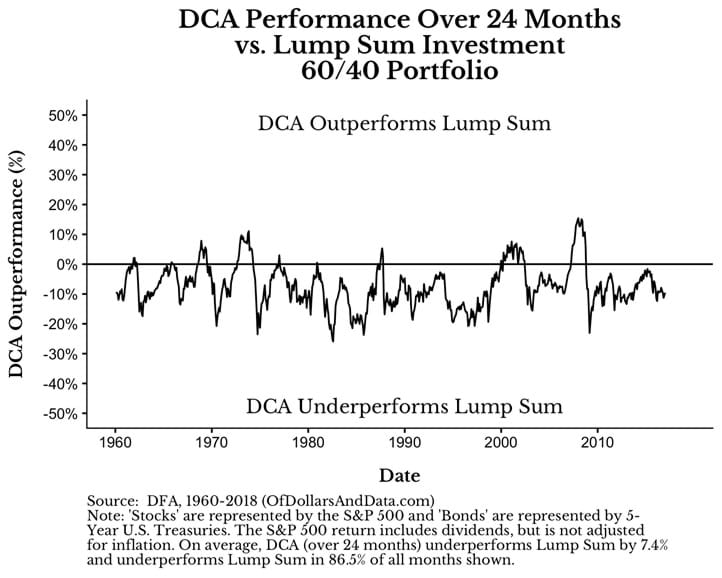

Lump Sum Investing > Dollar-Cost Averaging > “Buy the Dip” Timing

Exhibit #1:

Exhibit #2:

But don’t just take Nick’s word for it. Vanguard did a similar study a few years back and reached a similar conclusion.

So we know what the *data* tells us, but how do most FAs/clients typically behave when faced with a large lump-sum to invest? In my experience, some form of systematic dollar-cost averaging is often the path of least resistance. The larger the lump sum, the more likely that is the route taken. Sub-optimal? Probably. Should it be avoided at all costs? From a behavioral standpoint, probably not.

If You Missed the ______ Best Days

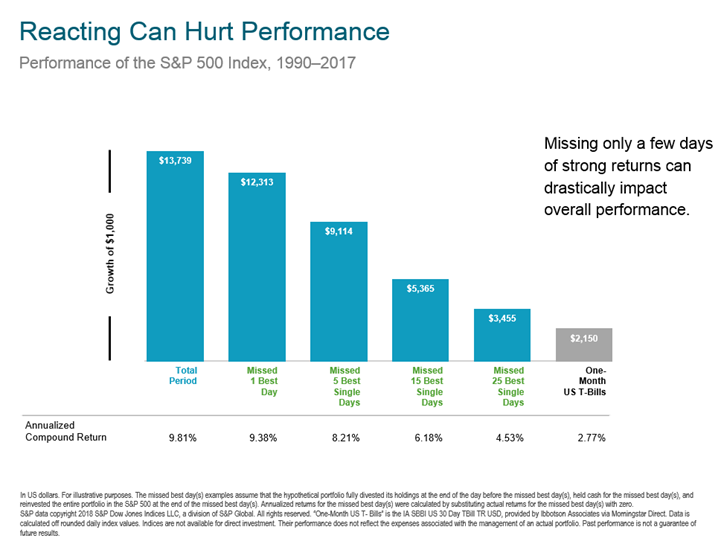

Every advisor on the planet has shared a version of the chart below at some point in their career. The punchline is that missing out on the best single days in the stock market can have a dramatic impact on your long-term performance.

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors

But does that resemble anything close to reality? Of course not. Nobody could possibly miss only the best 5, 15, 25, etc. single days. And as we know from market history, volatility tends to cluster to the upside and the downside. This means if you missed a lot of the best days, you likely missed a lot of the worst ones as well.

I’m not trying to pick on Dimensional for putting this together. When it comes to advisor-client communication tools, they are the industry gold standard. But I challenge you to find me any fund company that doesn’t have some version of this chart (or the infamous quilt chart) in their marketing literature library. And for good reason – because they’re effective. While not indicative of what any investor’s experience would actually be like, it hammers home the point that you’re never going to earn market returns if you’re not in the market in the first place.

“Asset Allocation Explains Over Ninety Percent of Returns”

In 1986, Gary Brinson, Randolph Hood and Gilbert Beebower (collectively known as BHB) published their seminal paper, “Determinants of Portfolio Performance.” The groundbreaking (at the time) study asserted that asset allocation was the primary determinant of a portfolio’s return variability. In fact, their research purported that ~95% of the variation in pension plan returns was attributable to overall investment policy, leaving less than 5% to be explained by market timing and security selection.

According to David Larrabee at the CFA Institute, “the BHB study went viral and almost immediately was incorporated into the marketing pitches of investment advisors.” Despite its widespread adoption, the study would go on to be challenged in academia with several critics claiming it was poorly understood and often misrepresented. Luminaries such as Roger Ibbotson conducted their own research to address some of the shortfalls of BHB, publishing “Does Asset Allocation Policy Explain 40, 90, or 100 Percent of Performance?” in 2000 and “The Importance of Asset Allocation” in 2010. The bottom line is that asset allocation still matters…a lot.

The original study had its flaws and its results were misinterpreted by many, but it sparked a wave of additional research that deepened our understanding of the impact that asset allocation has on returns. And if it kept a lot of people from otherwise engaging in the destructive behaviors of speculative stock picking and market timing along the way, then I think we can all agree it was a good thing.

Veiled De-risking

We’ve all been there before. You’re meeting with a client during a period of elevated market volatility. The client’s current asset allocation is aligned with their financial plan and no major life changes have taken place to warrant a material change other than the fact that they are a bit spooked by the market. So what do you do? Too dramatic of a shift might reduce the plan’s probability of meeting its goal, even if it allows the client to sleep better at night. An effective method from my experience is to do something, even if it’s just trimming a few percent from stocks. We all understand that the before and after portfolios are nearly one in the same, but the act of addressing the client’s concern in the heat of the moment allows them to live to fight another day without jeopardizing a well-crafted plan.

So what other benign myths are out there for financial advisors? Did I miss any big ones? Let me know in the comments or @ me on Twitter.

And be sure to listen to the full podcast episode with Patrick & Michael here:

Michael Mauboussin – The Four Sources of Alpha – [Invest Like the Best, EP.126]

Get on the List!

Sign up to receive the latest insights from Phil Huber directly to your inbox.