Does Farmland Belong in Your Portfolio?

This past weekend's issue of Barron's featured a piece from Lauren Foster on farmland investing with a few quotes from yours truly. The whole thing is worth checking out, but this pretty much sums up what's driving the current interest in the space:

"Two trends are driving the farmland investment thesis now: rising global demand for food and a shrinking supply of arable land. In the past 20 years, more than 11 million acres of U.S. farmland were lost to development. Climate-related factors such as water scarcity are also limiting the supply of arable land. At the same time, the world’s population is expected to top more than nine billion by 2050—and agricultural productivity will need to double to meet the expected global demand."

Agriculture is fascinating in the sense that it predates modern investing by multiple millennia and yet few investors have any material exposure to it in their portfolios. Per Norton Reamer and Jesse Downing, authors of Investment: A History:

"...we must understand that for many thousands of years, agricultural land was the primary store of wealth, source of income, and reservoir of gains for investors in ancient and premodern times. From Mesopotamia to Egypt, Greece, and Rome, it was the basic investment medium in early civilizations."

When we envision farmland, we often envision a small, family-owned operation. And for good reason—most farmland in the United States is owned that way, often passed down or inherited over multiple generations. But we may be in the early innings of a paradigm shift in the ownership of farmland, which is increasingly gaining mainstream acceptance as an institutional asset class.

Farmland has been historically difficult to access directly, as markets are thin and the costs of acquisition, management, and disposition are high. The market for farmland is still highly fragmented since institutional penetration has been slow-moving. As of 2021, the US Department of Agriculture estimated that institutional ownership represented just over 2% of the market. Farmland is also an incredibly low turnover asset class, with less than 1% of U.S. farmland trading hands annually.

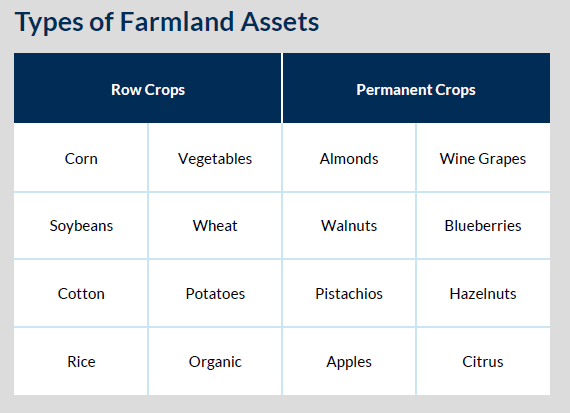

Setting aside livestock, farmland can be broken down broadly into two categories: row crops and permanent crops. Row crops, such as wheat, are typically planted and harvested on an annual basis. Permanent crops, as the name implies, refers to assets like perennial trees, vines and shrubs that produce things like fruits and nuts, which are grown and harvested over a multi-year horizon.

Source: Versus Capital

From an investment standpoint, there's a lot to like about farmland as an asset class:

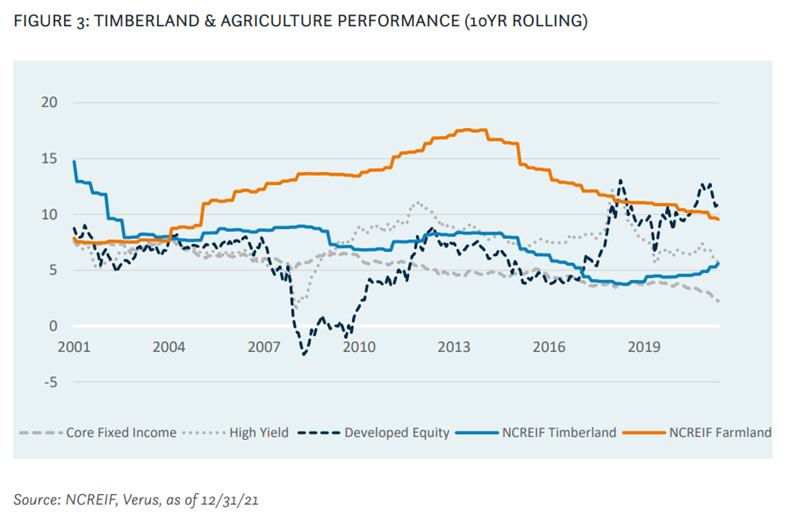

It has historically provided meaningful income and appreciation over time. The chart below plots the rolling 10-year total return of the NCREIF Farmland Index relative to developed public equities, core fixed income, high yield, and timberland. Income is the largest return component for farmland investors. This income can be variable, given the price volatility of the underlying commodities and their perishable nature. The appreciation of land value is the next largest contributor to asset returns. In short, there is less of it to go around—since 1950, U.S. farmland has dwindled by 25%. Improvements in productivity can also be accretive to total returns.

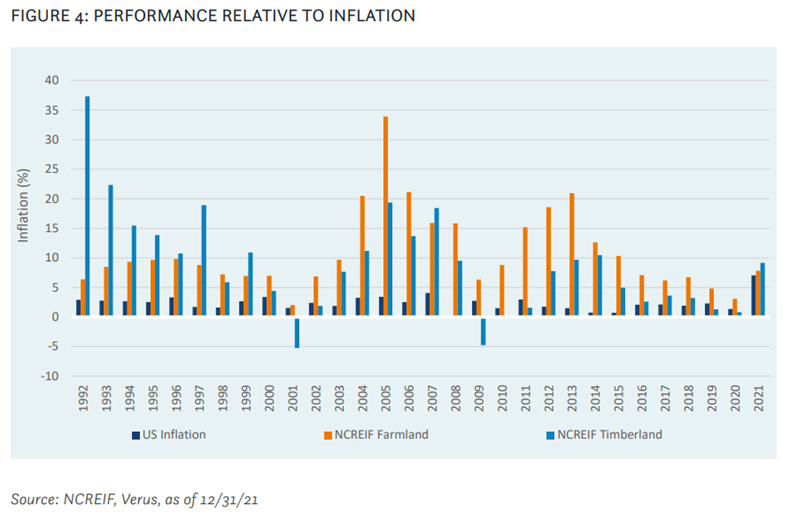

Positive sensitivity to inflation. According to Verus Investments, farmland has outpaced inflation in every calendar year since 1992.

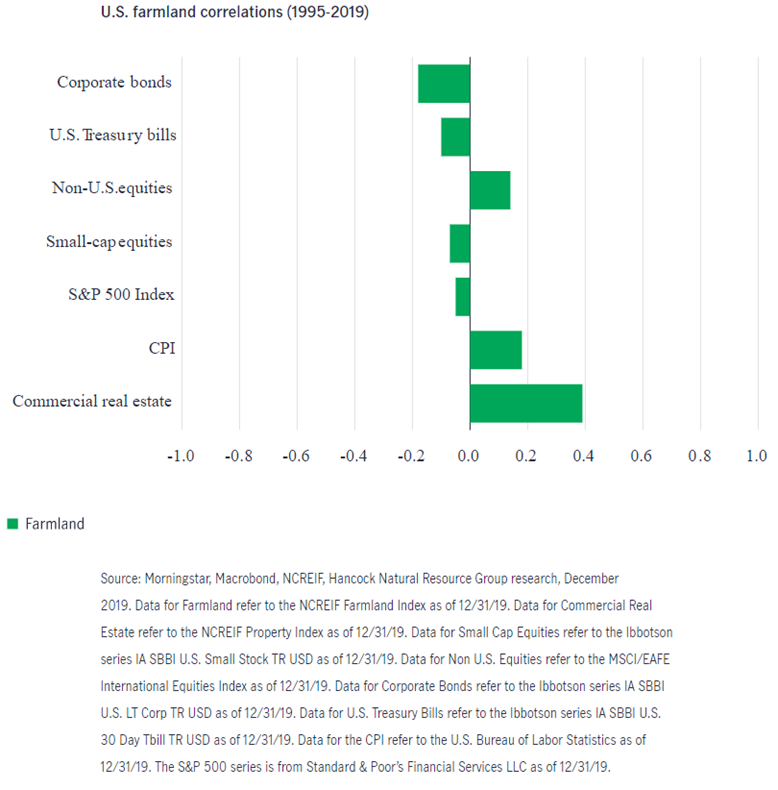

Low correlation to other asset classes. The diversification benefits of farmland have been meaningful. Research from Manulife Investment Management shows that the correlation of farmland to a host of other common asset classes has ranged from slightly negative to moderately positive.

Much of the investment thesis around farmland is related to supply and demand factors. The scarcity of arable land, coupled with population growth, an emerging middle class and the need for food security and animal protein, all give farmland unique properties as an investable asset class. In short, people need to eat.

Investors today have a growing number of options if considering the addition of farmland to their portfolios - publicly traded REITs, interval funds, private funds, ETFs that own agribusiness companies or hold agricultural-commodity futures contracts. There are even platforms like AcreTrader that offer individual farmland deals for accredited investors.

As elusive as farmland has historically been, one thing is for sure - the barriers to entry are coming down.

Ultimately, individual circumstances related to investor accreditation, liquidity preferences, investment minimums, etc. will dictate how investors are able to access the asset class.

Regardless of the access point, it stands to reason that farmland - with its long history and attractive investment attributes - will begin to make its way into more investor portfolios as an additional "real" asset to complement real estate and diversify core stock and bond exposures.

*Shameless plug alert*

I have an entire chapter on real assets - with a lengthy section specific to farmland - in my book, The Allocator's Edge: A Modern Guide to Alternative Investments and the Future of Diversification.

Pick up your copy today!

Additional Reading:

A primer: Timberland & farmland (Verus Investments)

Get on the List!

Sign up to receive the latest insights from Phil Huber directly to your inbox.