Hang in There

Resisting the urge to change course during inevitable periods of underperformance is one of the most difficult challenges investors face. Just as there is more than one way to skin a cat, there are several paths that can lead to success in markets. Take Value and Momentum for example, whose excess returns are driven by completely opposing forces. Both have worked well historically in spite of one another and even better when paired together – good enemies, better friends. Regardless of which flavor of investing your taste buds prefer, they all share one common denominator: nothing works all of the time.

One such approach that has come under fire quite a bit as of late has been asset allocation predicated on the concept of long-term mean reversion. Institutional Investor magazine recently ran a profile on one of the foremost purveyors of such methodologies, famed asset management firm GMO. While their long-term success is undeniable, they certainly have their fair share of both promoters and detractors. Fans of GMO will point to their track record of identifying market bubbles. Critics will be quick to point out that they are often very early, which to many in the investment community is pari-passu with being wrong. Love ’em or hate ’em, when they write/talk, people read/listen. That speaks to both the quality of their research and commentary as well as the steadfastness with which they apply their discipline. Here are a few highlights from the article:

Ben Inker, GMO’s co-head of asset allocation on why more managers don’t follow their approach and why

“The reason you don’t see a lot of money chasing long-term value strategies, particularly strategies like ours, is career risk…When it comes to challenging markets, we focus on reminding our clients that short-term under-performance happens,” says Inker, who has a calm but determined air. “The hard part is these conversations often take place just before markets start to look good to us in terms of investment opportunities.”

Jeremy Grantham, co-founder of GMO on the evergreen principles of value investing:

“Actually, not that much in investing has changed if you get down to it,” he says. “The nature of the beast is patience: Find out what are the cheap areas, avoid overpriced fashionable areas, and persuade the client to hang in.”

Inker on his commitment to GMO’s valuation driven philosophy (emphasis mine):

“One thing I’ve learned working alongside Jeremy is that you have to be patient. You can’t fall in love with a style of investing, but you can fall in love with a philosophy. I may change what I invest in over time, but I refuse to believe that valuations aren’t the key driver of assets over the long term.”

Matthew McLennan of First Eagle Investment Management, also interviewed for the article, on why human behavior will ultimately reap rewards for value investors with the stomach and discipline to stick with it through good times and bad:

“Individual ideas about how to assess value will always evolve. But fundamentally, value capitalizes on the fact that investors are extraordinarily talented when it comes to making bad decisions at the worst possible time. That won’t change.”

Arjun Divecha, who leads emerging-markets equity for GMO, on the counter-intuitive nature of when the value premium is earned:

“You make more money when things go from truly awful to merely bad than you do when things go from good to great,”

An unfortunate truism in our industry is that investors tend to abandon ship on an asset class or strategy right around the same time they should be piling into it. This isn’t unique to retail investors. Here’s a look at how some “highly sophisticated” institutions have reacted to GMO’s recent struggles:

“The lag in performance at GMO has caused a handful of U.S. public pensions invested across its strategies to put the firm on watch lists or terminate relationships completely. Firmwide assets sit at $99 billion, down from last year, when they hovered near $115 billion, and off substantially from 2007’s peak of $155 billion, according to Morningstar.

In May 2015 the $550 million Alameda–Contra Costa Transit District Retirement System, based in Oakland, California, unwound its tactical portfolio, which included GMO, citing performance. In March of this year, the $1.7 billion Milwaukee County Employees’ Retirement System terminated GMO’s $65 million mandate, also specifying performance.

The $12.1 billion Orange County Employees Retirement System in Santa Ana, California, has put GMO on its watch list; the firm manages $195 million for the pension.”

Each and every one of these institutions knew exactly what they were getting in hiring GMO and probably thought they were just as “long-term” and “contrarian” as they were. But then they got punched in the mouth. To paraphrase Rob Arnott, contrarianism in investing requires a preference for discomfort. And most investors learn the hard way just how much they love being comfortable.

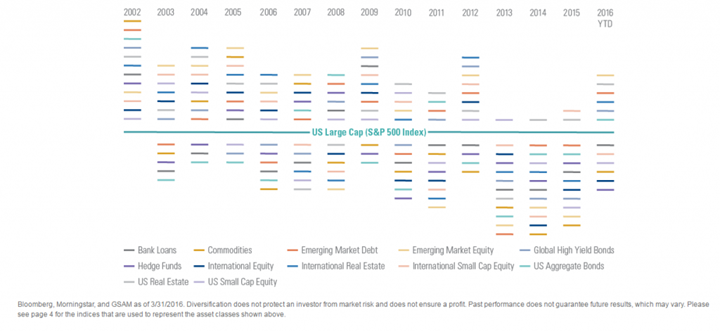

The folks at GMO aren’t alone in having their investment philosophies challenged in the market environment of the last few years. Many financial advisors (my firm included) advocate broad geographic diversification, in developed and emerging markets alike. The rationale being that since the US comprises roughly half of the global stock market, a significant overweight above and beyond that represents a sizable active bet. Over long stretches of time, this has historically been a prudent way to manage risk in an equity portfolio without having to sacrifice much -if anything – on the return side of the equation. Unfortunately, we are naturally wired to display what Patrick O’Shaughnessy refers to as Portfolio Patriotism. Also known as Home Bias, this phenomenon exists across the globe and becomes exacerbated when your home country’s stock market has been THE place to be in the recent past. The chart below from Goldman Sachs illustrates just how abnormal the last few calendar years have been as it relates to US Large Cap stock performance versus almost every other asset class. While diversification has paid off in several areas so far in 2016, the experience of 2013-15 has left many wondering if they’re better off just owning an S&P 500 Index fund and calling it a day.

Source: Goldman Sachs

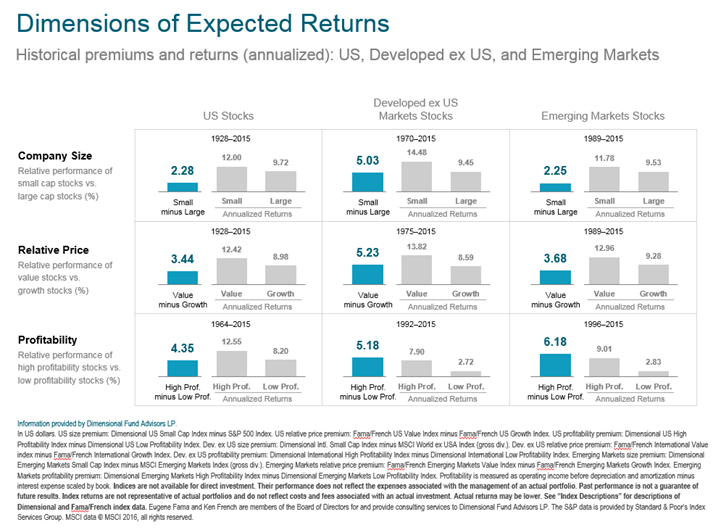

Actively overweighting, or “tilting”, towards stocks that exhibit certain factors is another example of an asset allocation decision that is backed by considerable evidence but has recently fallen on hard times. Below are the historical annualized excess returns earned in the US, Developed Ex-US, and Emerging Market stock markets for the following factors:

- Company Size (the difference in return between small-cap stocks and large-cap stocks)

- Relative Price (the difference in return between value stocks and growth stocks)

- Profitability (the difference in return between high profitability stocks and low profitability stocks)

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors

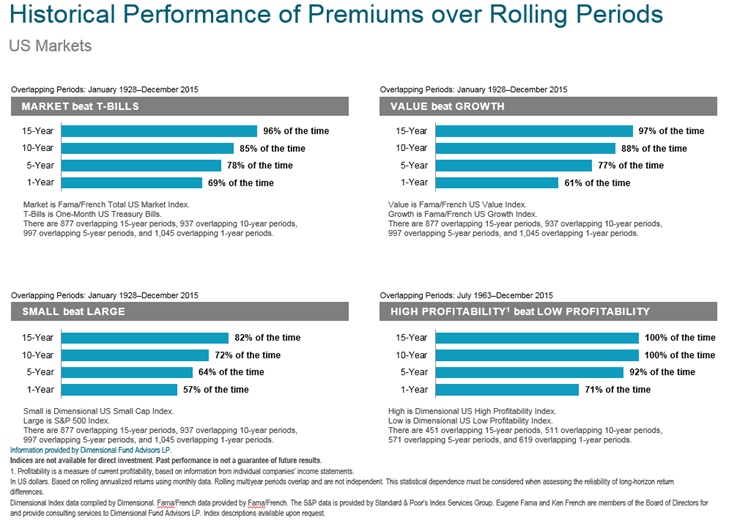

The numbers associated with each of these factors are certainly compelling, particularly when you take into account that they have persisted over multiple time periods and across many markets. But these return premiums are earned, not given. Much like the return of the market itself, they do not show up to work every day and lunch with them is never free. The image below shows that whether you’re looking at Size, Value, Profitability or the market itself, your odds historically of earning a positive premium in any given twelve month period – while certainly higher than a coin flip – are not a lock. What is evident, however, is that the longer you extend out your time horizon, the higher your probability of success becomes.

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors

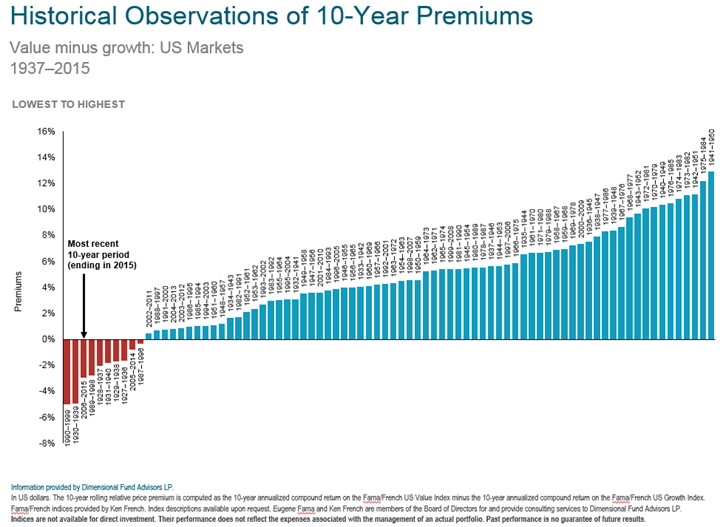

But highly probable is not synonymous with guaranteed. Let’s take a closer look at the Value Premium in the US stock market. The graph below plots all historical observations of the 10-Year difference between Value stocks and Growth stocks. The blue bars represent a positive Value Premium and the red bars a negative premium. While certainly a rarity, there have been several 10-Year periods where the Value Premium flat out didn’t show up, and we just lived through one. In fact, the negative value premium in the US from 2006-2015 has only been lower twice in history – the Great Depression and the Tech Bubble.

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors

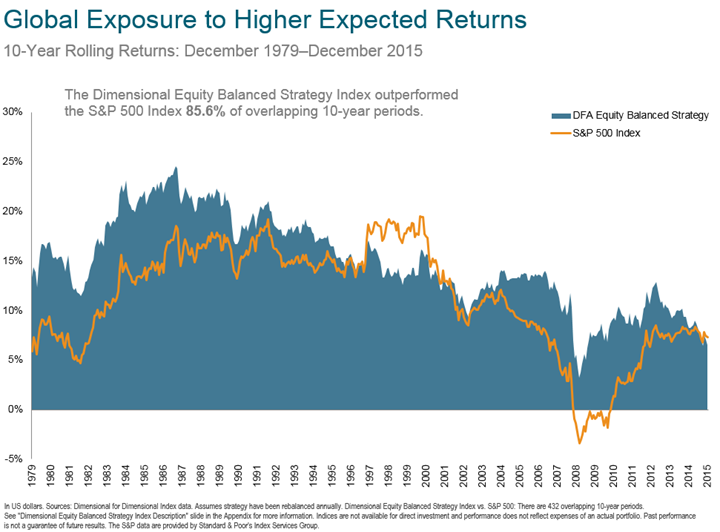

So back to the question facing many investors today: why not just own the S&P 500? Because of this:

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors

A prudent approach to equity investing is more than an exercise in growing and compounding wealth. It also means managing risk in such a way that your odds of having less money than you started with after a decade plus in the market are minimized. The DFA Equity Balanced Strategy* highlighted above – in addition to outperforming the S&P 500 in over 85% of rolling 10-year periods – has never lost money over such a horizon. No “lost decade” there. What’s more, there were two full decades – the 70’s and the aughts – in which an investment in the S&P 500 earned you less than one-month T-bills. Diversification is guaranteed to frustrate in any given year but can provide much more control over your range of long-term outcomes.

The moral of the story is simple. No matter what kind of investor you are, there is going to come a point in time when you question your own conviction. When that time comes, remember why you chose to invest the way you did by revisiting the evidence that supported it in the first place. If there was none, then perhaps it’s time to go back to the drawing board. But if there was and still is, then the best thing you can do is take your eyes off the rear-view mirror and hang in there.

GMO’s Mean-Reversion Strategy Is Tested in Today’s Market (Institutional Investor)

(Full disclosure: My firm, Huber Financial Advisors, recommends funds from Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA) in constructing client portfolios.)

*The Dimensional Equity Balanced Strategy Index is comprised of commercial and Dimensional indices, 70% US equity indices, and 30% non-US indices. US: S&P 500, large cap value, small cap, small cap value, Dow Jones REIT; non-US: international value, international small cap and small cap value, emerging markets, and emerging markets value and small cap. Additional index information is available upon request. Rebalanced monthly

Get on the List!

Sign up to receive the latest insights from Phil Huber directly to your inbox.