The Four C's of Investment Costs

Alternative investments are generally more expensive than stock and bond funds. I'm not breaking any new ground here.

In a world where passive market beta is effectively free, investors rightfully place a greater degree of scrutiny on investments that at first glance seem relatively pricey.

Like anything in life, there is a place for low cost and a place for higher cost. Sometimes we want a burger from McDonald’s and other times we splurge on a bone-in ribeye from a nice steakhouse.

All else equal, the lower the cost the better - more money in our pockets. The challenge in investing is that all else is rarely equal. Trade-offs must be weighed and evaluated, and the costs of any investment must be contextualized. To help with this conversation, I like to frame fund expenses in terms of what I call the Four C’s of Investment Costs: Capacity, Craftsmanship, Complexity, and Contribution.

- Capacity: The amount of capital a strategy can prudently oversee without degrading its integrity is of paramount importance to its cost. The reason market-cap weighted U.S. large-cap stock index funds are essentially free is because they have near infinite capacity. So, while the expenses as a percentage are infinitesimal, from a dollar standpoint they can create meaningful revenue for an asset manager given the incredibly large base they have to charge it on. Conversely, asset classes like catastrophe reinsurance aren’t as scalable. To offer such a strategy at Vanguard-like fees would not be profitable.

- Craftsmanship: For nuanced strategies, implementation and design choices can make all the difference between success and failure when translating something that works on a spreadsheet into the real world. Fees should be commensurate with the level of detail involved in the development and execution work needed to maximize efficacy and minimize slippage.

- Complexity: Assets with a higher degree of embedded intricacy typically require oversight and management from people with highly specialized talent, knowledge and expertise that are not as plentiful as found in other well-trodden corners of investing. Higher degrees of compensation naturally accompany useful skills that are in high demand and scarce supply.

- Contribution: Investments that are structurally uncorrelated to things people already own and that offer meaningful risk premiums are valuable and thus should command a premium price. The more differentiated and additive to the portfolio, the more willing you should be to pay up.

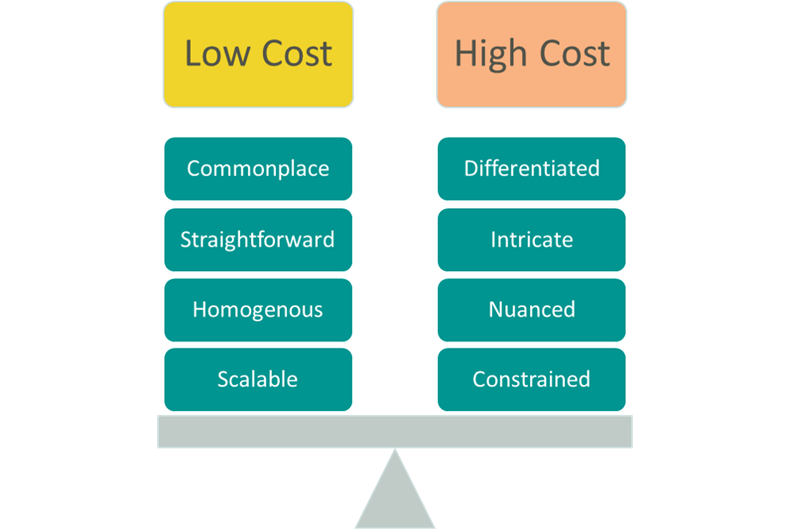

The visual below summarizes the main features of low-cost and high-cost assets:

When evaluating the expenses of different investment products, we must avoid comparing apples and oranges, or worse yet apples and orangutans. The expenses of an S&P 500 ETF should have no bearing on whether a managed futures mutual fund is deemed reasonable or overpriced. Similarly, a "smart beta" ETF that costs 20 bps might appear dirt cheap at first glance. But if you look under the hood, you might discover that for all intents and purposes the fund isn’t that much different than the broad market—which you can own for 3 bps. In this scenario, you are paying a great deal for the minimal amount of active risk being taken. On the flip side, the price tag for a liquid alternative mutual fund might seem steep at 1.25%, but when measured against a similar hedge fund that charges 2 and 20 it could be a bargain.

Costs can be a tricky subject to navigate when selecting funds and building portfolios. What’s important is that you don’t overpay for things you can get for much cheaper. When you do decide to pay up, make sure you have a high degree of confidence the expected benefits will survive the additional costs. As Cliff Asness has stated, “there is no investment product so good gross, that there isn’t a fee that could make it bad net.”

Get on the List!

Sign up to receive the latest insights from Phil Huber directly to your inbox.