This Is What It Sounds Like...When Funds Die

A common refrain in investing circles is to comment that there are too many mutual funds and/or ETFs in existence.

"Why do investors and allocators need tens of thousands of funds to choose from?" they might say.

And they'd be right.

But what gets lost in that conversation is that the fund landscape would be even more humongous were it not for one key factor: the hundreds of funds that die every single year.

The investment graveyard is littered with the corpses of failed funds. (sorry for the morbid visual, but we're close enough to Halloween)

Daniel Sotiroff and Ryan Jackson of Morningstar recently authored a beast of a research report that analyzed mutual fund and ETF closures over a fifteen year period (2005-2020) and sought to discover what, if any, shared attributes these deceased funds had in common. It's an important, yet overlooked, topic. This should be obvious, but as the report's authors point out:

Dead funds don't compound investors' capital, let alone beat the market.

In addition to performance related concerns, dead funds also come with potential headaches related to unexpected tax bills and the opportunity cost of reallocating if not paid attention to.

So what did the authors discover? Let's take a look...

(Editor's Note: Given the liberties I took with the lyrics of When Doves Cry in the title of the post, it seems only fitting that my summary of the paper be accompanied by GIFs of Dave Chappelle cosplaying as Prince.)

Age and Size Matter

Two clear patterns emerge from the data the authors analyzed:

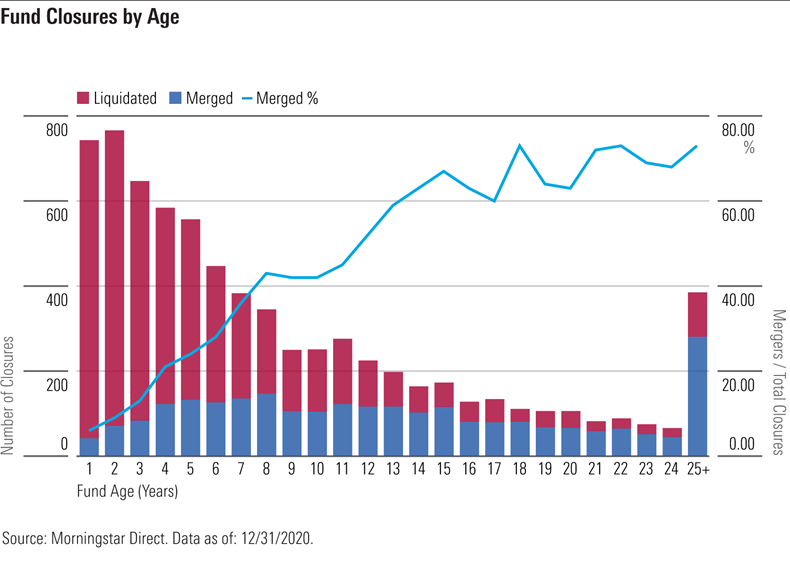

- Younger funds are more likely to die

- Smaller funds are more likely to die

It's safe to assume that there is a fair degree of overlap between those two characteristics.

When launching a new fund, it's ok in the short term to have a low asset base. But as time goes on, the fund eventually needs to reach a critical mass where the revenue generated covers the costs of running it.

Timing luck can make or break a new fund. Some get lucky and catch lightning in a bottle by hitting a home run or capturing the current investor zeitgeist. Others may be conceptually sound, but are unfortunately ahead of their time. Regardless, new funds have a finite window to capture investors' attention.

Old funds die too, but those usually come in the form of being merged into another fund. There seems to be a Lindy Effect in the mutual fund world. The longer a fund sticks around, the more likely it is to keep sticking around.

Poor Performance and Excessive Risk Taking

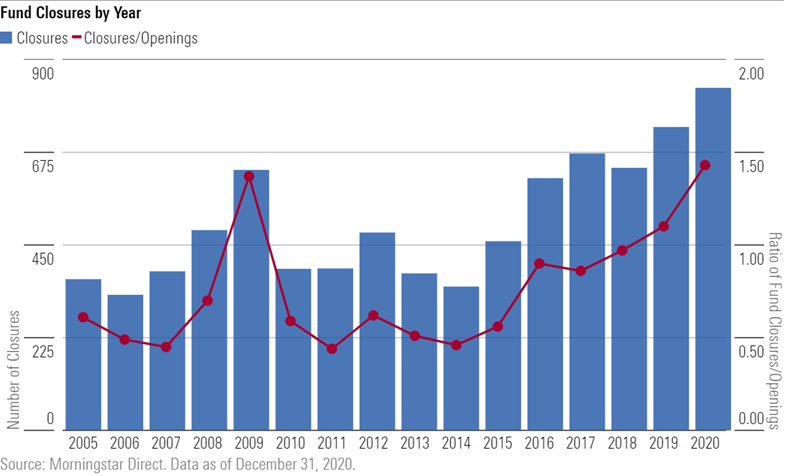

While the number of fund closures has been steadily rising in recent years, there are notable spikes in years of crisis. The 2008-09 period saw an abnormally large number of closures.

An underperforming fund or one taking excessive risk may be forgiven (or go unnoticed) in a bull market as the rising tide lifts all boats.

But when the tide goes out...well, you know the Buffett quote.

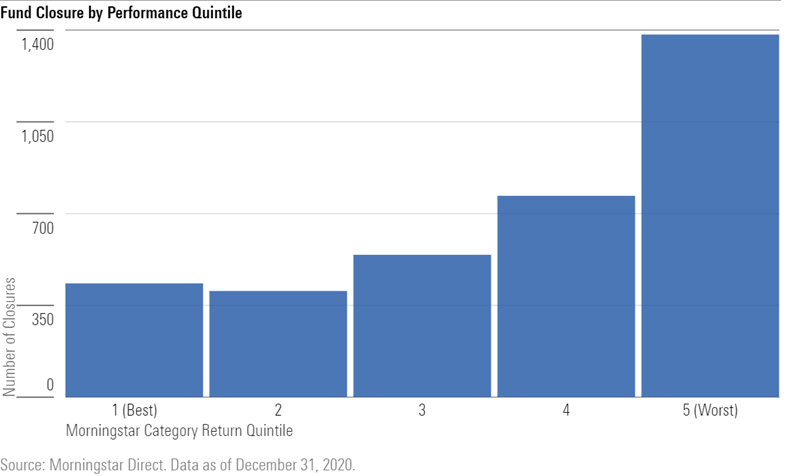

The authors discovered a pretty clear (and intuitive) relationship between closures and performance relative to category peers. The chart below depicts the number of closures by quintile, with the first quintile being the best relative performers and the fifth being the worst relative performers.

Fund Provider Type

Dodge & Cox is an old-school mutual fund manager that's been around since 1930. They have over $300 Billion in AUM and have never closed a single fund.

Their secret? They've only opened 7 of them.

On the other hand, the giant, supermarket fund complexes that try to be all things to all people have to consistently develop new products out of necessity. They're also large enough to be able to withstand and afford closures, so they're more inclined to throw spaghetti (and macaroni and penne and ravioli) at the wall to see what sticks.

It doesn't mean one business model is right or wrong. They're just different.

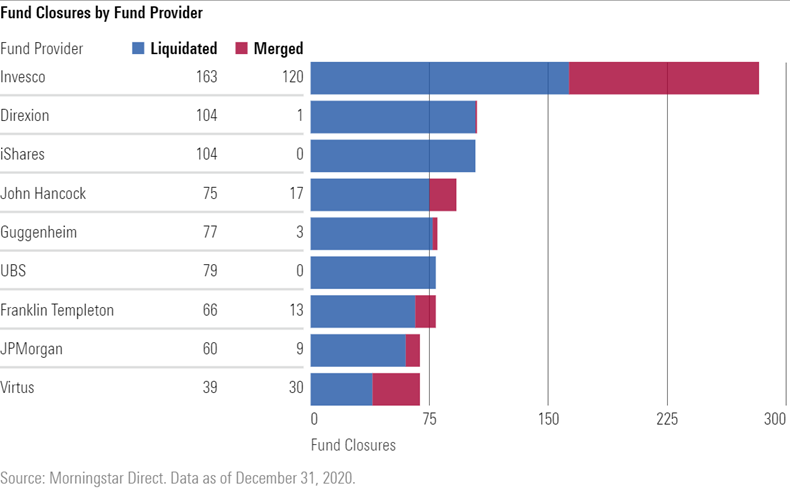

M&A activity is also a major driving force in fund closures, particularly when it comes to fund mergers as opposed to outright liquidations.

Shops like Invesco for example, who has been on an acquiring spree, typically end up consolidating funds from the lineups of their targets in asset classes and strategies where there is overlap.

Fees, Fees, Fees

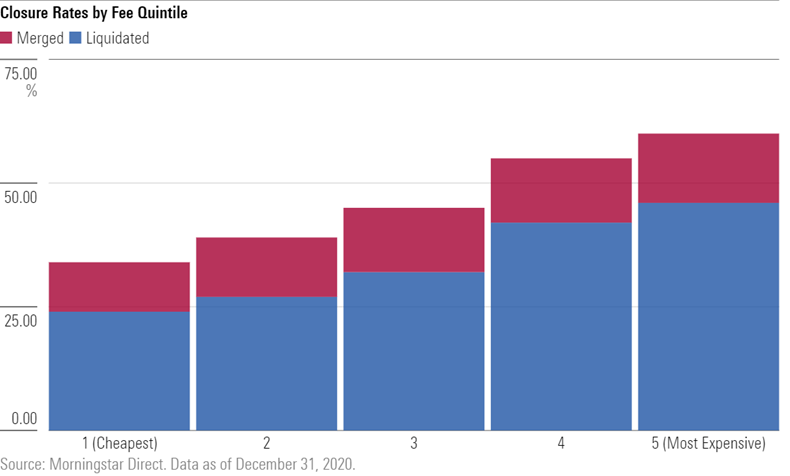

If there has been one dominant trend in investing the last 20 years, it's been that of declining fees. So it goes without saying that funds that have yet to purify themselves in the form of more reasonable expenses are more likely to have the marketplace do it for them.

Sure, there are some categories that are naturally more expensive than others. But the last thing you want to be is among the most high-priced cohort within your respective category. Per the authors, funds in the most expensive quintile had a closure rate of more than 60 percent over the last 15 years!

Can Allocators Avoid Dead (or Dying) Funds?

Natural selection is just as pervasive in asset management as it is in evolutionary biology. While there are some measures investors can take to try and side step funds that are destined to meet their maker, the risk cannot be avoided completely.

Many funds go on to live long, fruitful lives. Others, despite their best efforts, eventually give way to the headwinds they are up against. When the Grim Fund Reaper comes knocking, it's game over.

Interested in learning more? Below is an article from Morningstar as well as a link to the paper itself:

Article: Why Funds Die (Morningstar)

Full Paper: Why Funds Die: A Closer Look at the Traits Associated with Fund Closures

Get on the List!

Sign up to receive the latest insights from Phil Huber directly to your inbox.